Oceans: An Opera of the Depths

By George Willis csc, asc

It’s indeed sometimes strange how events come together. Philippe Ros AFC was at an awards ceremony in Israel when he thought he recognized a name on one of the information boards that of his long lost school friend Philippe Lavalette csc. After 30 years he was finally able to make contact with him. Through a sequence of events, Lavalette was instrumental in arranging for Ros to travel to Canada under the auspices of Rendezvous-vous du Cinéma Québécois Film Festival, which arranged for Ros’s stay in Canada. Lavalette, who resides in Montreal, then contacted CSC President Joan Hutton csc. That is when I took over.

It’s indeed sometimes strange how events come together. Philippe Ros AFC was at an awards ceremony in Israel when he thought he recognized a name on one of the information boards that of his long lost school friend Philippe Lavalette csc. After 30 years he was finally able to make contact with him. Through a sequence of events, Lavalette was instrumental in arranging for Ros to travel to Canada under the auspices of Rendezvous-vous du Cinéma Québécois Film Festival, which arranged for Ros’s stay in Canada. Lavalette, who resides in Montreal, then contacted CSC President Joan Hutton csc. That is when I took over.

I tracked down Ros with the idea of arranging a screening of the remarkable film Oceans coupled with a Q&A session. I had heard about Oceans – that it was a technological marvel of cinematic splendour. Digital imaging director and one of the 17 cinematographers, Ros was pivotal in the making of the underwater epic. But I didn’t realize how pivotal and significant his job was until our first few conversations.

Oceans was an enormous and complicated undertaking. Its logistical and technological scope was mindboggling. It was a seven-year undertaking with principal shooting beginning in 2005. It required 340 weeks of filming over a five-year period in 54 locations around the world. Oceans involved 17 cinematographers, including 10 underwater specialists, with up to six-to-eight units shooting simultaneously. Many of the production’s camera rigs and tools were developed and custom-built for Oceans to solve an array of movement and image conformity problems. Ros was quick to point out that the success of Oceans relied heavily on the participation and collaboration of his colleagues.

This collaboration was fostered by the film’s two directors, Jacques Perrin and Jacques Cluzaud, who had a singular vision when Oceans was initially discussed. The mandate was simple: photograph the various scenes in ways that had never been done before; become a fish among the world of the fish and not merely an observer. For those of us who are divers, this is not just another film about the underwater world, the ‘inner space’ as it is often called. Oceans is arguably the most significant underwater feature film since the groundbreaking work of Jacques Cousteau in his 1956 documentary The Silent World, where underwater cinematography was used for the first time to show the ocean deep wonders in colour. The Silent World was the first of Cousteau’s two films to win Academy Awards for best documentary feature, the other being World without Sun in 1964.

This collaboration was fostered by the film’s two directors, Jacques Perrin and Jacques Cluzaud, who had a singular vision when Oceans was initially discussed. The mandate was simple: photograph the various scenes in ways that had never been done before; become a fish among the world of the fish and not merely an observer. For those of us who are divers, this is not just another film about the underwater world, the ‘inner space’ as it is often called. Oceans is arguably the most significant underwater feature film since the groundbreaking work of Jacques Cousteau in his 1956 documentary The Silent World, where underwater cinematography was used for the first time to show the ocean deep wonders in colour. The Silent World was the first of Cousteau’s two films to win Academy Awards for best documentary feature, the other being World without Sun in 1964.

Since The Silent World 35 years ago, the business of underwater filmmaking has seen very significant changes, not only in film and video technology but also in the development of diving technology. Modern divers are now able to utilize re-breather equipment, which allows for closer intimate views of sea life. Prior to the re-breather technology, traditional SCUBA diving equipment, with its cloud of exhaled bubbles, tended to frighten away underwater creatures. Interestingly, the SCUBA system (first called the Aqualung) was invented by Jacques Cousteau and Emile Gagnan in 1942.

Since The Silent World 35 years ago, the business of underwater filmmaking has seen very significant changes, not only in film and video technology but also in the development of diving technology. Modern divers are now able to utilize re-breather equipment, which allows for closer intimate views of sea life. Prior to the re-breather technology, traditional SCUBA diving equipment, with its cloud of exhaled bubbles, tended to frighten away underwater creatures. Interestingly, the SCUBA system (first called the Aqualung) was invented by Jacques Cousteau and Emile Gagnan in 1942.

My nascent Internet relationship with Ros quickly evolved into a fascinating learning adventure. The more we spoke, the more captivated I became with Oceans. I downloaded and read the Film and Digital Times article on Oceans (April 2010) by John Fauer asc. I had all of Oceans press releases, studied the promo photos and I had read the article in American Cinematographer (May 2010). I figured I had a handle on what to expect from Oceans. Then a Blu-ray version of Oceans arrived in the mail from Paris from the film’s executive producer, Olli Barbé. Not long after settling down and watching Oceans on my big-screen television did I realized just how much more my expectations were being exceeded. It soon became apparent that this wasn’t just an amazing film about the world under the sea, but that it was an extraordinary, mesmerizing film about the oceans, capturing their sublime gentleness and raw fury.

It is difficult to know where to begin when describing Oceans because each magnificent visual seems to surpass the previous. Right from the opening, where prehistoric creatures emerge from the ocean’s inner space to take the stage alongside the launch of a modern-day rocket headed for outer space, the film’s magnificent visual juxtaposition style is set. We see spectacular, powerful images of ships crashing through mountainous seas in the tempeste sequence, shot from a helicopter by cinematographer Luc Drion sbc, to the intimate and gentle image of a mother and baby walrus in tranquil artic waters.

There is a scene showing two blue whales, the giants of the sea, in a beautiful lyrical scene. While the sequence is stunning, we were given an even bigger treat during Ros’s Q&A. We were shown a separate full-length take where the camera captures the complete poetic ballet of these magnificent leviathans. As a diver and underwater cinematographer, this certainly brought a tear to my eye as well as goose bumps. I cannot imagine what the underwater cameraman Didier Noirot must have experienced as he witnessed and captured this most stunning and magical sequence. Truly that must have been an experience of a lifetime.

Once again, the juxtaposition of visuals takes us from the gargantuan creatures the size of 747 jets into the microscopic world inside a single drop of water photographed by Ros himself. The scene that unfolds would have us believe that we are in the cosmos, drifting by some alien forms as a planet comes into frame, its shape defined – which is actually the outside of the water droplet – with hard-edge reflected light presumably emanating from a large terrestrial source. In a shark sequence, shot by underwater cinematographers David Reichert and Didier Noirot, an intrepid diver builds up trust with a Great White shark and then swims alongside the 12-foot monster; a creature we are always taught to fear and regard as a killer.

Dolphins stir up the ocean like a cauldron as they race along the foaming surface to where a mass of sardines is swarming in a huge organized school. But chaos ensues as hoards of birds dive into the water like bullets and surface with their trophy meals. Dolphins squeal and feed alongside the birds; sharks arrive to claim their share; and then the whales appear. Just before we leave the scene, an aerial shot shows the boiling surface as the feeding frenzy continues, in grand style for a grand feast.

From the inky blue depths where the big fish reign supreme, Oceans takes us to the intimate habitats of the smaller creatures of the reefs. Through the very naturalistic lighting by Ros, we witness the symbiotic relationship between the clown fish and sea anemone to the pugilistic sequence between the peacock mantis shrimp and a brave but foolish crab, which meets its demise. In another reef scene, shot by underwater cinematographer René Heuzey, we see hundreds, if not thousands, of crabs, two phalanxes approaching one another like opposing troops from a scene in The Lord of The Rings until they merge into a mountainous mass of crustaceous body parts.

Like an eye, a siphon emerges from a large spider shell monitoring the environment and soon the single muscle uses its strength to flip the shell over while a hermit crab enters the frame, finds an abandoned shell and climbing inside, claims it as its new home and scuttles away. Venomous lion and stonefish strike out with lightning speed at unsuspecting prey, while a ribbon eel puts on a dazzling dance display. Night comes to the reef and new life emerges with the creatures that inhabit their domain; Joe the Crab moves about the coral heads with scuttling purpose known only to itself.

Extreme close-ups of many different species show in exquisite details what nature has provided to the small creatures of the reef for a myriad of purposes, from feeding to camouflage. It’s the survival of the fittest; or should that be the fishiest, because some of these creatures captured on film barely resemble what we assume to be fish. In the bright light of day and in another ocean, seals cavort and penguins speed through crystal clear water like jets in a clear blue sky. Pure white beluga whales gather under the ice as a group of pointy nose narwals, the unicorns of the sea, gambol in an icy opening. A lone polar bear doesn’t feel like company as it dives into the frigid waters, protected by its hollow hair strands.

The visual content of Oceans is far too lush and expansive for words to do it justice. Oceans needs to be seen relished and understood for the cinematic marvel that it is. While there is a voice track, I find it superfluous and unnecessary in a story that can be told through its images. Some refer to Oceans as a feature film, others call it a documentary; but to me, it’s a magnificent lyrical opera.

The Diver and the Camera

By George Willis csc, asc

The spectacular underwater visuals in Oceans have been captured in a variety of ways, from specially designed rigs and camera systems to the basic SCUBA diver operating a camera underwater. While setting aside the technical aspects for a moment, let us concentrate on the requirements to capture an underwater scene.

The spectacular underwater visuals in Oceans have been captured in a variety of ways, from specially designed rigs and camera systems to the basic SCUBA diver operating a camera underwater. While setting aside the technical aspects for a moment, let us concentrate on the requirements to capture an underwater scene.

It goes without saying that the diver’s specific qualifications and certifications are not only a must but in most cases are a legal requirement for safety reasons. The underwater environment can be as tranquil as a pond but also as violent as a churning sea, and the diver has to be prepared to deal with both.

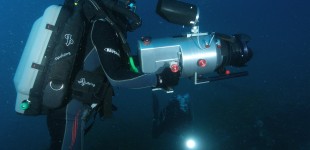

Underwater cameras are essentially regular cameras that are placed in waterproof housings. Above water, these units can weigh anywhere from 50 pounds to well over 150 pounds. However, when underwater, these same units can weigh almost nothing because of the air contained within the housing. In fact, the actual weight of the housing in the water is approximately two pounds, resulting in a slight negative buoyancy.

Why the buoyancy factor? The simple explanation is that a diver should be neutrally buoyant if he is able to hover in the water. Adding or subtracting lead weights worn around the diver’s waist, until the diver attains a hover position, accomplishes this buoyancy control. Once the diver has the camera housing in his hands, further fine tuning of the overall weight can now be achieved by the diver adjusting the air within his buoyancy compensator, which also serves as a piece of safety equipment. This results in the diver and the housing being in a stable free floating and weightless position, hence the term ‘inner space.’

But this attitude of hovering brings its own set of idiosyncrasies, bearing in mind that the photographic requirement is for the camera movement to be as stable and smooth as possible. The slightest movement of the diver will result in movement of the camera and unless that movement is controlled, the resulting image could not only be bumpy and distracting, but also be rendered unusable through bad operating.

Herein lies the key to underwater camera operating. The diver has to forget that he is a diver and leave behind all thoughts of being in an underwater environment, encumbered by life-sustaining equipment, breathing through a mouthpiece, having little peripheral vision, potential mask-squeeze, ear pressure equalization and being too conscious of buoyancy control. There is only one thing to focus on, and that is the scene unfolding before him. SCUBA diving has to be second nature, yet the diver has to be able to react at a moments notice to any given factor, which might compromise his safety.

While maintaining a swimming position, as opposed to a hovering position, the diver must not only pay attention to the framing of the subject and obtain a smooth movement while finning, but also pre-empt any possible movement of the image in his viewfinder.

Let us take, for example, from the diver’s perspective, the requirements when photographing the two blue whales. Cinematographer Didier Noirot brings buoyancy skills into play as he maintains his hover state while filming this sequence. But during the lengthy uncut sequence, because of his perfect buoyancy, he will be able to fill his lungs, thereby rising in the water or exhale in order to bring himself to a lower level. Judging from the sequence, the variance in depth of the diver is anywhere between 60 and 120 feet.

The camera in this sequence is extremely steady and controlled throughout the varying depth and serves to acknowledge the diver’s superb buoyancy control and his ability to equalize (an absolute physiological must) without relinquishing hold of the camera. This description only touches on the very basic requirements of shooting underwater, but it serves to underline the complexities that have to be dealt with when attempting to capture some of the extraordinary imagery in Oceans.

Complexities that arise when shooting underwater include the smaller creatures of the reef, which demand even more stringent control of the camera movement. There are situations when one can obtain extreme close-ups of reasonably stationary sea-life. But where unpredictable creature movement is concerned, the handheld camera, in its large and awkward housing, simply is not a very viable option or solution. We then have to address the special camera requirements and resort to different approaches in which to capture those visuals that stand out from the ordinary.

The various specialized rigs, shooting techniques other groundbreaking technology that were used in the production of Oceans will be described in depth in the next issue of Canadian Cinematographer.